Story by Bruce Mooers with Photos by Michael Alan Ross.

This story first appeared in the July/August 2025 issue of Hagerty Drivers Club magazine. Join the club to receive their award-winning magazine and enjoy insider access to automotive events, discounts, roadside assistance, and more. Here is the link to the article on Hagerty’s website.

~ If you are a Hagerty member, you may have seen this article in your latest Drivers Club Magazine featuring our very own Bruce Mooers and his Yenko Stinger. If you have not had the chance to read it yet and see the photos, enjoy!~

When I was looking for my first car in the late 1970s, I took an interest in the Corvair because it was a Bill Mitchell design with an air-cooled rear engine at a price I could afford. I bought my first one, a 1963 Corvair Monza, when I was 15. I was on my own to maintain it and keep it on the road, so I started to buy tools and began tinkering. In doing so, I fell in love with the Corvair’s simplicity and uniqueness. These cars tend to hook people, and I’m no exception. I have seven of them in my garage now.

I’ve owned around 40 Corvairs over the years, everything from Monzas to the turbocharged Corsas and Spyders, but I always wanted a Yenko Stinger. In 1966, before he was known for putting big-blocks in Camaros, Don Yenko purchased 100 white Corvairs through GM’s Central Office Production Order and then prepared the cars for racing.

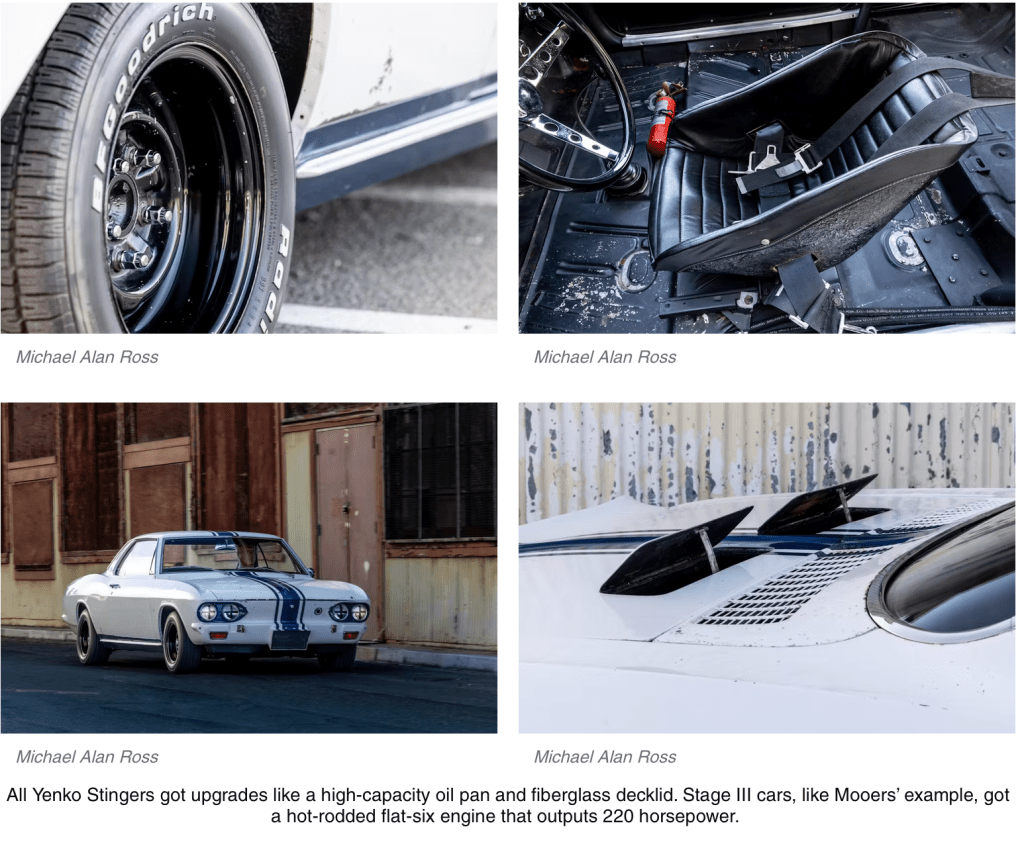

The Corvairs were available in various stages of tune, with their flat-six engines outputting anywhere from 160 to 240 horsepower. To comply with Sports Car Club of America rules, the Corvair’s rear seats were removed. The Stingers were very successful in their class and outperformed imports like the Triumph TR4. An additional 15 cars were prepared between 1967 and 1969. Many Stingers have since disappeared, rotted away, or were wrecked.

I figured I would never find one, but a few years ago, some pictures of a barn-find Stinger had surfaced on the Corvair club forums. A lot of the members didn’t believe the car was real, but I started digging for the owner’s contact information. The guy proved to be elusive, but while I was in Columbus, Ohio, traveling for business, a club member passed along the phone number for the Yenko owner. I was warned the owner was ornery, because apparently some members of the community called to tell him that his Stinger was a fake. But I called as soon as I could, and I was able to talk him into letting me see the car. It was serendipity, really, that the Stinger was only 45 minutes away in Mansfield.

The next day, I drove to see the owner. We went around back and the Yenko Stinger was in the garage. It hadn’t been driven since 1971 and had only 3500 miles on the odometer. Luckily, there was no rust or body damage. I knew what to look for, how to read the data plates, and I understood the build sequence of the cars, so I could verify that the car was legitimate. The blue stripes, Yenko tag, fiberglass racing seat, roll bar, dual-circuit master cylinder, oil cooler, racing carburetors with velocity stacks—all of it was there and all the numbers matched. This was a completely original Stage III Stinger. So I bought it on the spot because I didn’t think I would get another chance.

I shipped the Stinger back to California and began working to get the car back on the road. The 220-hp Stage III engine turned over by hand, but I was afraid to start it because I had no idea why the car had been parked for so long. Curiously, when I pulled the engine and disassembled it, I didn’t find any damage. So I photographed all the components and then put it all back together.

While the motor was out, I removed the brake system, gas tank and lines, and suspension so I could deep-clean the undercarriage. I was glad the Stinger was stored in a garage, because every bolt just came right off. The gas tank and all the lines were replaced, and I sent the brake wheel cylinders and master cylinder to White Post Restorations in Virginia for repair. I powder-coated the front and rear suspension after I disassembled it all, and I installed new bushings, Koni shocks, and springs.

The exhaust headers, which are rare pieces from Cyclone Racing, were sandblasted and recoated white. Longtime Corvair racer Bob Coffin helped me rebuild the carburetors, and Stinger expert Jim Schardt helped me verify several key components on the car and provided me with a set of vintage Goodyear Blue Streak racing tires for show use.

Putting the car back together took some time, but it wasn’t difficult work. I got the Stinger roadworthy last summer, and it runs perfectly. Late-model Corvairs handle well, but the Yenko, with its quick steering arms and fast ratio box, is a blast on the back roads around Napa Valley. It’s a loud car, so I coast through my neighborhood before I turn it on. But once I am on the open road, the exhaust note is glorious.

My sons and I look forward to many years enjoying the Stinger and sharing it with the Corvair Society of America and its members, as well as the rest of the classic automotive community. We want to keep it in the condition that it’s in, but we aren’t afraid to drive it on the weekends or maybe take it to a track day. Sometimes I’m tempted to restore the car and make it perfect. But Yenko Stingers are rare, and an all-original example is even more so. I have to remind myself that once you restore a car, you can’t undo it. I’d prefer not to erase this Stinger’s history.

Leave a comment